Last month I was given a wonderful opportunity, receiving a Patient Advocate Scholarship from the Conquer Cancer Foundation to attend this year’s 50th American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting. As an independent advocate, I’m usually in the position of needing to cover my own expenses. The result is that there are far too many important meetings I’d like to attend every year that I simply cannot, so I often have difficult choices to make. It was for that reason that I hadn’t been able to attend ASCO’s Annual Meeting for a few years—so I was delighted to be on my way to Chicago to attend the sessions in person again, rather than following the news remotely.

ASCO 2014 Annual Meeting

The ASCO Annual Meeting is always a valuable conference and, for the oncologists who attend, it can be practice-changing. When I first attended the ASCO Annual Meeting as a new advocate, it left a tremendous impression on me. The sheer numbers of people streaming through the immense McCormick Conference Center, the different languages I heard all around me, the dozens of sessions occurring simultaneously, the camera crews interviewing oncologists about breaking news, and being right there in the audience, often with thousands of others, hearing long-awaited findings from critical clinical trials—all around, it was an invaluable experience for me as a survivor as well as a committed cancer research advocate. But by far my most lasting impression resulted from my discussions with several fellow advocates who were also attending ASCO—some for the first time like myself and others who had been present every year for decades. I had attended several breast-cancer-specific conferences by that time and had made many lasting friendships with breast cancer advocates. But the ASCO meeting was the first time that I’d met a large number of advocates whose efforts focused on so many different types of cancer—pancreatic, lung, ovarian, and esophageal cancers, lymphomas, leukemias, and others. And I found that of course, there were important differences in focus depending on the form of cancer: for example, the very real concerns about stigma impacting lung cancer patients, due to an unspoken feeling by some that they have somehow “caused themselves to have cancer by smoking”; the fact that there are smaller numbers of advocates and resources for pancreatic cancer, lung cancer, and other cancer types due to the unfortunate reality of poor survival rates and numbers of patients; and this names just a few. BUT I was immediately struck by how much we all shared, having similar concerns, challenges, passions, and frustrations—and by how much we all could learn from and teach one another. Thanks to that first ASCO meeting, I made friendships with many advocates that will last a lifetime, and we have all reached out to one another over the years since for advice, to share resources, to offer advocacy opportunities, to connect newly diagnosed patients with important support, and to collaborate on critical advocacy efforts.

And all that I just described held true for me during this year’s meeting: how gratifying it was to be surrounded by so many who are dedicating their lives to treating, preventing, and curing cancer; to see dear advocate friends again and to meet talented new advocates who are performing such crucial work; and to participate in and witness new collaborations and partnerships being formed between advocates, researchers, clinicians, and all stakeholders in the cancer landscape.

But …

Something happened during this year’s ASCO meeting that was quite literally heart-wrenching. And it painfully brought into focus my changing perspective as a now older, perhaps more “hardened” advocate.

The moment occurred when I was sitting in the audience with hundreds of other people during a session entitled, “50 Years of Advances in Breast Cancer Treatment: What Have We Learned? Where Are We Going?” And the fact is that in the last decade alone, we have made critical advances and learned so much about the biology of breast cancer, which in turn ultimately led to crucial new treatment approaches–perhaps most notably, trastuzumab (Herceptin®) for the targeted treatment of HER2+ breast cancers. But as I listened to the speakers, I found myself reflecting on how much we still do not know. Are we just now only learning the right questions to ask? What about the terrible reality of resistance that often develops to new agents, including targeted therapies–and of tumor dormancy for ER+ breast cancers that, in about one-third of patients, ultimately leads to a diagnosis of metastatic breast cancer often decades after a patient’s original diagnosis? And what about what many call the incrementalism that impacts cancer research, where the investment of many years and millions of dollars, as well as the involvement of tens of thousands of cancer patients in clinical trials, may lead to a drug approval based on just weeks’ improvement in overall survival or on surrogate endpoints? Most importantly, what about the fact that we do not yet have a cure for metastatic breast cancer?

Celebrating my 4th birthday with my first cousin (the cutie with the blond hair) and friends

To break my chain of thought, I glanced down at my cell phone, planning to quickly check my messages and then turn my full attention back to the speakers. And that is the moment when I saw the message that broke my heart and turned everything around me grey. My first cousin, my best friend when we were little, the one I worshipped, had just been diagnosed with metastatic HER2+ breast cancer. As I sat in that conference room, and the speakers continued to talk about the crucial advancements made for breast cancer patients in the last 50 years, and the audience members all around me were taking notes, snapping pictures of the slides, talking about the presentation, or simply listening, I was angrily wiping tears from my face, thinking over and over to myself, “It’s not enough! It’s nowhere near enough! My cousin, my friends with mets, everyone with BC mets, they need a cure, and they need it NOW!”

These thoughts stayed with me during the remainder of the meeting, including when I was listening to what was perhaps the most reported session in the media—a session that made everything even greyer. It was during this session that Dr. Martine Piccart-Gebhard reported the long-awaited results of a large, multicenter phase III study called the ALTTO trial, which randomized over 8,000 women with HER2+ breast cancer following surgery to either concurrent trastuzumab and lapatinib (Tykerb®), trastuzumab followed by lapatinib, or trastuzumab alone for one year. The patients in the trial received anti-HER2 therapy either after completing all chemotherapy, concurrently with a non-anthracycline, platinum-based regimen, or concurrently with anthracycline followed by a taxane. (A fourth arm of the trial, where lapatinib alone was compared to trastuzumab, was closed due to futility in 2011.)

Dr. Martine Piccart-Gebhart presenting the first ALTTO Trial Results

When Dr. Piccart-Gebhard presented these first results of the ALTTO trial during this meeting, she announced that the results disproved the hypothesis that dual anti-HER2 therapy with trastuzumab and lapatinib in the adjuvant (postsurgical) setting enhances clinical outcomes in patients with early-stage HER2+ breast cancer. She reported that at four years, disease-free survival, the primary outcome of the trial, was 86% with trastuzumab alone, compared with 87% with trastuzumab followed by lapatinib (*P=.610, hazard ratio, 0.96) and with 88% with concurrent trastuzumab and lapatinib (P = .048; hazard ratio, 0.84).

Median overall survival rates were 94% with trastuzumab alone and 95% with both combination treatment arms. Dr. Piccart-Gebhart also reported that lapatinib was associated with significant increases in diarrhea, skin rash, and liver events, stressing that this may explain why just 60% to 78% of patients in the lapatinib-receiving arms of the trial received at least 85% of the protocol’s specified dose.

In other words, the primary endpoint of disease-free survival was not statistically significant—i.e., no better with the combination of these two specific HER2-targeted agents when compared to trastuzumab alone—and furthermore, lapatinib was associated with more side effects. These results were a serious disappointment, and the expert commentary grimly emphasized the significance of the information gained from this trial.

*What is a P value and hazard ratio?

In most studies, a P value of less than .05 is selected to determine statistical significance, meaning that if the data show that the “null hypothesis” has less than a 5% chance of being correct, then it is wrong. The null hypothesis is the hypothesis that an observed difference is due to chance alone and implies no effect or relationship between phenomena. A hazard ratio is the measure of how frequently a specific event occurs in one group compared to how often it occurs in another group over time. In cancer clinical trials, hazard ratios are frequently used to measure survival at a particular point of time in patients who have received a specific treatment compared to a control group who received another treatment or placebo. A hazard ratio that equals 1 indicates that there is no difference in survival between the treatment and control groups, with a ratio of more or less than 1 meaning that survival was better in one of the groups. Together, the P value is used to reject the null hypothesis that the hazard ratio equals 1—that is, that the treatment being studied is not beneficial.

Invited discussant Dr. George Sledge, Jr., former president of ASCO and chief of oncology and professor of medicine at Stanford University Medical Center, reminded the audience of the thrilling moment during the 2005 ASCO Annual Meeting, when the first results were announced for adjuvant treatment of early-stage HER2+ breast cancer with trastuzumab, the first anti-HER2 targeted therapy. He described this as a “defining moment in our field,” where the associated 50% reduction in the annual risk of recurrence still “remains one of the great success stories.” But “there was still real work to be done,” and he emphasized that such efforts involved evaluating biology-based approaches, explaining that the combination of trastuzumab with kinase inhibition “at the time appeared to be the best bet.” (Kinases are enzymes that activate proteins by “signal transduction cascades,” when a molecule outside a cell activates a specific receptor either inside the cell or on its surface. Activation of the receptor then triggers a cascade of events inside the cell, which may alter gene expression, the cell’s metabolism, or its ability to divide, for example.) Lapatinib is an anti-HER2 agent that inhibits the intracellular tyrosine kinase domains of both the HER2 and HER1 receptors. Because lapatinib inhibits two cell surface receptors and is a smaller molecule than trastuzumab, the hope was that it may prove to be more effective when combined with trastuzumab through the two agents’ different mechanisms of action, achieving dual HER2 blockade.

Dr. George Sledge Jr., former President of ASCO, Discussant for Plenary Session on the ALTTO Trial Results

This led to the development of the ALTTO trial, comparing use of trastuzumab alone against the combination of trastuzumab and lapatinib and, ultimately, the findings that there was no significant difference when lapatinib was added to treatment. Dr. Sledge emphasized that the ALTTO trial required a strict P value of .025 or less to demonstrate statistical significance, and he stressed that no one should be misled by the disease-free survival P value of .048, thinking that this was a positive trial. Rather, he firmly stated that “This is a negative trial.” He then posed the important question of whether this trial might later turn statistically positive with further follow-up based on additional results. His response: “Perhaps, but not very positive, given the results we’ve seen today.”

The negative results of the ALTTO trial were surprising due to the positive results of the earlier NeoALTTO trial, a study in which lapatinib and trastuzumab were compared with trastuzumab alone in the presurgical (neoadjuvant) setting. Treatment with lapatinib, trastuzumab, and paclitaxel (Taxol®) was found to nearly double the pathologic complete response rate (pCR). (Pathologic complete response, or no invasive or in situ residuals in the breast or lymph nodes, is proposed as a surrogate endpoint of tumor response that should be strongly correlated with more traditional endpoints such as overall survival and disease-free survival.)

These results are not only extremely disappointing based on lack of improvement with this specific combination therapy; rather, they also raise troubling questions on the approach to the development of new drugs for early breast cancer. As Dr. Sledge noted, these negative findings “tell us at a simple level that we won’t be using lapatinib in the adjuvant setting,” since as discussed above, he predicts that further follow-up of the ALTTO trial results will not lead to a statistically significant positive result. But he also stressed that these findings have produced several larger, critical questions: “You might be wondering why a negative adjuvant trial occupies a Plenary Session spot, a place usually reserved for practice-changing data. I suggest that the answer requires us to rethink our approach to the development of new drugs for early breast cancer. ALTTO represented a reasonable test of the hypothesis that improvements in pathologic complete response rates were associated with improved disease-free survival. These hopes have now been dashed.”

Said another way, in recent years, many breast cancer researchers, clinicians, and advocates have become increasingly comfortable with the idea of conducting innovative, smaller neoadjuvant clinical trials, using pCR as a surrogate endpoint to predict outcomes in the adjuvant setting. Yet the negative results from the ALTTO trial, following the positive results from its sister neoadjuvant trial, NeoALTTO, serve to undermine confidence in the accuracy of predicting and translating treatment effectiveness and outcome from one clinical setting to another. As Dr. Sledge noted, the ALTTO trial “invites a larger question” of whether agents that are found to be effective in the metastatic or neoadjuvant settings can be considered predictive of similar efficacy as adjuvant treatments. “Why have these approaches failed in the adjuvant setting, despite a plethora of preclinical evidence and numerous positive trials in the metastatic setting that show an overall survival advantage? These setbacks should prompt us to ask, are we facing a systemic crisis in the adjuvant failure of targeted therapies or just having a string of bad luck?”

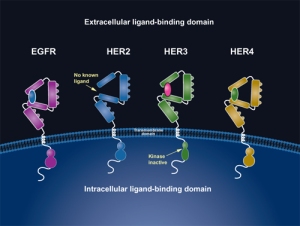

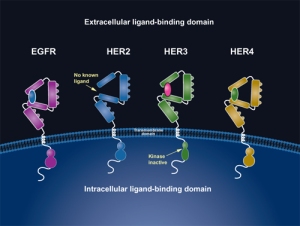

ErbB family of receptors

Dr. Sledge went on to emphasize that results from another large adjuvant trial, called the APHINITY trial–which is also studying the efficacy of dual HER2 inhibition versus use of a single anti-HER2 agent–will be of great interest in light of ALTTO’s negative results. APHINITY is a large Phase III randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial that is comparing the efficacy and safety of chemotherapy, trastuzumab, and placebo against chemotherapy with trastuzumab and pertuzumab (Perjeta®) as adjuvant therapy in patients with HER2+ primary breast cancer. Like trastuzumab, pertuzumab is a monoclonal antibody that targets the HER2 receptor, but it binds to a different part of the HER2 molecule and thus does not compete with trastuzumab. Pertuzumab prevents the pairing (called “dimerization”) of HER2 with other HER (ErbB) receptors (HER1 [EGFR], HER3, and HER4), particularly the pairing of HER2/HER3, blocking the signaling pathways within the cell that lead to tumor growth.

And in fact, as I wrote in a previous blog posting, “All eyes will indeed be on the large adjuvant APHINITY trial …,” because last year, for the first time for any cancer, FDA approval was given to an oncologic agent—i.e., pertuzumab– in the neoadjuvant setting, based on pCR as a primary endpoint. This was in no small part because of the ongoing, fully accrued APHINITY trial, whose results, if successful, could support conversion to regular FDA approval or, if negative, will even further emphasize the need to completely re-evaluate our current approach to drug development and clinical trials for agents to treat early breast cancer.

On this last point, when the Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee (ODAC) voted on whether to support Accelerated Approval for pertuzumab in combination with trastuzumab and chemotherapy for neoadjuvant treatment of HER2+ breast cancer, many ODAC panel members (including myself as the patient representative on the panel) stressed a critical point: that if the results of the APHINITY trial were in fact negative, the sponsor, Genentech, should voluntarily remove pertuzumab for the neoadjuvant treatment of early-stage breast cancer. As our committee chair, Dr. Mikkael Sekeres, emphasized to the FDA, “All eyes will be on the confirmatory APHINITY trial and on you to verify this initial signal of efficacy and to confirm the bandwidth of safety that we have seen so far.”

In light of the ALTTO findings, APHINITY’s long-awaited results will now carry even more impact, whether they are positive or negative. In concluding his discussion, Dr. Sledge emphasized that trial failures such as ALTTO “must be elucidated in order to move forward and create new successes.”

At this writing my cousin has received two treatments thus far with chemotherapy, trastuzumab, and pertuzumab. And in her husband’s words, per her oncologist’s first assessment of her response, “the couple centimeter lump of cancer on her neck” (which had resulted in her stage IV diagnosis) “has gone away.” I pray daily that this means she is a strong responder to dual blockage with trastuzumab and pertuzumab. I pray that some day she’ll hear the words that her stage IV breast cancer is now “NED,” meaning No Evidence of Disease. And I pray that in the words of Dr. Sledge, “ … Move forward, we shall, in HER2+ positive breast cancer” and that the many novel approaches actively being researched today will move us closer to the day when we have finally found a cure or cures for stage IV breast cancer–for my cousin, for my far too many friends with this disease, and for all those with stage IV disease. Please pray with me.