Many folks might not understand this. But I’ve lost track of how many times I’ve thanked God that I and not one of my loved ones was the cancer patient. After being diagnosed with lymphoma shortly after college, cancer shaped my life. As I’ve said many times, being a cancer survivor has impacted every adult decision of my life: staying in a job that I disliked far too long due to fear of being without health insurance, my decision to become a medical writer, when to get married, and on and on. But I’ve had to be matter-of-fact about this. Cancer, its late effects, what seems like my bimonthly thyroid biopsies, the number of daily pills I’ll always have to take, my long list of specialists—it’s simply my reality. But that’s okay. Long ago, I subconsciously made this one of my roles: I took on the role of cancer patient, the one with the chronic health issues in my family, with the understanding—or perhaps more accurately stated, the magical thinking—that I gladly accept this role to protect any of my loved ones from EVER experiencing cancer, cardiac issues (another of my late effects), or any serious chronic health issue. My message to myself was “I’ve got this. I’ve got my family covered.”

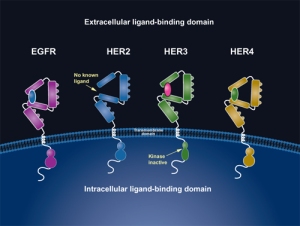

My mother helped me to understand this at a more conscious level just last year, one which was very difficult for my family. I have two female first cousins, one on my mother’s side and one on my father’s side—and in one year, they both were diagnosed with stage 3 HER2+, ER+ breast cancer at the age of 49. I was never angry about my own cancer diagnosis: the first time, my thought always was, “Well, why NOT me?,” and the second time I’d long understood that I had a greatly increased risk for breast cancer due to my radiation treatment as a young woman. But when I learned that my first first-cousin had just been diagnosed, I was distraught and absolutely furious. I literally screamed when I heard the news. And when I learned a few months later that my second first-cousin had been diagnosed as well, my anger and distress were even blacker and deeper. I couldn’t understand my reaction, and I pushed it down deep, because it was critical to me to be strong for my cousins and able to have my “advocate hat” firmly in place to provide all the possible information, resources, and support I could for them both. But in talking with my mother one day, I shared with her how deeply furious I was that they were both going through this and how confused I was about feeling this way. She said that she had the answer, asking “You don’t remember what you said to me, do you?” Of course, I’m notorious among my family for not remembering anything (thank you, “chemobrain” parts 1 and 2), so we chuckled over that. She then explained that shortly after my breast cancer diagnosis, she’d asked me why I wasn’t angry about being diagnosed now for a second time. And she reminded me of my answer: “You said that as awful as it was, you knew you’d get through it, and you weren’t at all angry because, after all, that must mean that you had the family covered.”

And that’s true: I continue to pray every day that that’s IT—that cancer has learned now who’s boss and will not DARE touch another of my loved ones. This may explain why I was so struck by something a fellow cancer survivor and advocate said during a panel discussion last year, where we were both participating as Patient Advocate Fellows during the Drug Information Association (DIA) annual meeting. When my new friend and colleague, Deborah Cornwall, began her portion of our panel’s presentation, she explained that she was a breast cancer survivor, but that her own “brush with cancer was trivial” compared to the caregiver and patient stories she’d had the honor of hearing while working on her recent book, “Things I Wish I’d Known: Cancer Caregivers Speak Out.” She explained that although there were so many books for the cancer patient, as there should be, there were very few for the cancer caregivers–for the spouses, the parents, the children, the siblings. As Deborah discussed her book, its purpose, and the meaning that it had for her and the many caregivers she interviewed, I was deeply moved, thinking about just how important this book was—that in addition to the patients themselves, it’s just as critical that the loved ones who are caring for them receive the support they need and how cancer also turns their worlds upside down.

A few weeks following the conference, Deborah graciously agreed to an interview, during which I asked her about the genesis of her book, any critical overarching themes that arose while speaking with the caregivers, and the experience itself of speaking with so many people about what was often the most heartbreaking time of their lives. Following is some of the conversation that Deborah and I had, including several quotes from Deborah and the caregivers themselves.

Cancer Caregivers Speak Out

“Why do people love firemen? People love firemen because when everyone else is running out of a burning building, they’re running in. It’s easier to run away. Caregivers are running into the burning building…”

~Chuck’s Mother

In the introduction of Deborah’s book, she shares the following, describing the beginning of the caregiver journey:

“Most caregivers describe their reactions to a loved one’s cancer diagnosis in violent terms: a fast-moving or violent physical assault, a punch in the stomach, a car hitting a deep pothole at high speed, a hijacking, an earthquake, a lightning strike, or a vicious animal bite. A few mentioned a sensation of being frozen and unable to move, or feeling as though a rug had been pulled out from under them.

“If you have been suddenly thrust into the caregiver’s role, you may have experienced similar sensations when a loved one or close friend received the cancer diagnosis. There’s so much information coming from all directions that you may feel overwhelmed, angry, or bewildered. ‘Normal’ has just disappeared from your life. You may be fantasizing that you’ll wake up tomorrow and find out that this was all a bad dream. You may even feel resentful: After all, you didn’t sign up to set your own life aside to become a caregiver.

“Your emotions are real, and confronting them is the first step in coming to grips with your caregiver role. You’re probably wondering how this unexpected journey will go, and how it will end. You may be looking for support, guidance, or help—perhaps for the first time in your life—at the same time that you’re uncertain where to look, or even what to ask for.

“That’s another reason why I’ve written this book.”

“In reading about the key issues you’re likely to face and what others did when encountering similar situations, you’ll have the opportunity to learn from their approaches and use them in creating your own solutions to your unique caregiving challenges. While this book won’t serve as a complete ‘how-to’ guide or steer you to every resource you might need—caregiving often requires invention under pressure—it will provide guidance and build your confidence in inventing your own way.

“I was honored that the people I interviewed chose to share their stories and life lessons. Their candor and intimacy were unexpected gifts that enriched my life immeasurably and made this book a reality. In turn, I share their reflections with you in the belief that they will help you on your journey. Their hard-earned insights, their indomitable hope, and their desire to help others to stay focused in the face of adversity represent their way of giving something back to those who helped them.”

~Deborah Cornwall, Marshfield, Massachusetts, 2012

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Our interview began with Deborah’s sharing how “Things I Wish I’d Known” came to be:

“Writing a book of some sort actually came from my aunt, who is 95 years old now. So she was about 91 when the idea came up. I was talking with her about various experiences that I had had at Hope Lodge, [which provides] free lodging for cancer patients and their caregivers who come in from more than 30 miles away for regular care for cancer treatment…I had been involved on the American Cancer Society Board of Directors in New England when we decided to build the [Hope Lodge in] Boston. I kind of adopted it personally. My husband and I would go there periodically to serve holiday meals, because our daughter lives elsewhere and can’t always be with us. While there, I would always meet people whose stories were just amazing and far more dramatic than my own. Afterward, I would share them with my elderly aunt on the telephone. Then one day, she said, “You have got to write a book” … I kind of pooh-poohed it, because your relatives always believe you can do anything. But a few weeks later, after the idea had had time to germinate, I realized she was right.”

In thinking about the shape that the book would take, Deborah realized that there were few books that specifically focused on the stories of the cancer caregivers, how they coped, what resources were most helpful to them, and, upon reflection, what they wished they had known beforehand but learned only in the midst of their experiences as a caregiver. So that is the book that she wanted to create. Deborah noted, “That’s when I charged off on my own and said, ‘Okay, I need to find people who are willing to talk to me.’ She explained that with HIPAA (the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) privacy regulations, “that’s a bit tricky. So I needed to spread information out in the right places and let people know how to contact me if they were interested in talking about their experiences.”

In thinking about the shape that the book would take, Deborah realized that there were few books that specifically focused on the stories of the cancer caregivers, how they coped, what resources were most helpful to them, and, upon reflection, what they wished they had known beforehand but learned only in the midst of their experiences as a caregiver. So that is the book that she wanted to create. Deborah noted, “That’s when I charged off on my own and said, ‘Okay, I need to find people who are willing to talk to me.’ She explained that with HIPAA (the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) privacy regulations, “that’s a bit tricky. So I needed to spread information out in the right places and let people know how to contact me if they were interested in talking about their experiences.”

Deborah stressed that the sourcing of interviewees was itself a fascinating process. “I think the most interesting piece of it was that in addition to posting invitations at several of the Hope Lodges, I would also send out waves of emails to groups of my own contacts, asking them to spread the word. I got a phone call one day from a woman who had received my email, which I’d sent to someone out of state, who forwarded it to somebody else in another state, who in turn forwarded it to the woman who called me. It turned out that on the third forwarding, it went to [this woman] who lives five minutes from my house! Isn’t that bizarre? So there are all sorts of fascinating procurement stories in terms of finding these people.” Deborah went on to share another example of such serendipitous connections: “I received a phone call from a woman who had just lost her husband. [She’d been] in a park walking with her daughter and newborn son, and a friend of mine happened to be passing through that city when they met and created the connection. This woman has sustained our relationship and become a good friend. There were all sorts of really random types of connections, but essentially, when I got to 86—and there was nothing magic in the number–I thought to myself that I’m hearing the same things frequently enough that I believe I have enough to work on. So that was the genesis.” In the second edition of the book, Deborah added another nine conversations focused on healing, bringing the total to 95.

Deborah stressed that the sourcing of interviewees was itself a fascinating process. “I think the most interesting piece of it was that in addition to posting invitations at several of the Hope Lodges, I would also send out waves of emails to groups of my own contacts, asking them to spread the word. I got a phone call one day from a woman who had received my email, which I’d sent to someone out of state, who forwarded it to somebody else in another state, who in turn forwarded it to the woman who called me. It turned out that on the third forwarding, it went to [this woman] who lives five minutes from my house! Isn’t that bizarre? So there are all sorts of fascinating procurement stories in terms of finding these people.” Deborah went on to share another example of such serendipitous connections: “I received a phone call from a woman who had just lost her husband. [She’d been] in a park walking with her daughter and newborn son, and a friend of mine happened to be passing through that city when they met and created the connection. This woman has sustained our relationship and become a good friend. There were all sorts of really random types of connections, but essentially, when I got to 86—and there was nothing magic in the number–I thought to myself that I’m hearing the same things frequently enough that I believe I have enough to work on. So that was the genesis.” In the second edition of the book, Deborah added another nine conversations focused on healing, bringing the total to 95.

Deborah emphasized how moved she was that so many caregivers were willing to speak with her for her book. “I was stunned at how eager people were to talk and how much they wanted to share with me, usually as a complete stranger. Two-thirds to three-quarters of the caregivers were complete strangers with not even a personal referral connection, not even a mutual friend . It was really stunning to me how eager they were to pour out their most intimate life stories. And what it said to me once I got going was just how important they thought the book could be.” She also noted that during their caregiving experiences, “some of these caregivers were deserted by people they thought they were close to. So I think that in some ways, that made them want to talk about it more, because family members or friends didn’t know what to say and didn’t know how to have a conversation about what the caregivers were going through. In a way, to talk to a stranger who really wanted to know what happened was nourishing to them. After one particularly moving conversation, one interviewee said he felt better because it felt as though he’d just been to therapy. It had presented the opportunity to voice things that he’d kept inside since his wife had died. I think that the interviews did allow people to get in touch with how they had really navigated the experience when maybe they really hadn’t had the opportunity to reflect on it before.”

In fact, folks were so open to speaking with Deborah about their caregiving experiences that her first interview for the book occurred even before she thought she was prepared. “My first interview was with a woman I’d known for years who was on the staff of the American Cancer Society. Just before a scheduled meeting started, I [mentioned] to her that I was writing a book on caregivers. Her immediate response was, ‘Oh, I’m a caregiver. Talk with me! I have time right after the meeting is over.’ My first thought was, ‘So soon? I haven’t even finished the interview guide yet!,’ but I did it. Her story was a rich one. She had been the primary caregiver for her father, who was dying of cancer, and at the same time for her mother, who was having a nervous breakdown. My friend was a single mother of two young children, she had two siblings who were uninvolved, and she was trying to work at the same time. At one point, I asked her, ‘Where were your siblings? Did they ever ask how you were doing during this whole process?’ It took her several minutes to respond. Then she looked at me with these wide deer-in-the-headlight eyes, and all of a sudden, tears started rolling down her face. That’s when I realized that I was on to something really important.”

Deborah shared that when she completed and submitted the initial draft to her professional editor, his feedback was positive, yet she was taken aback when he stressed that, ‘It’s only twice as long as it can afford to be to get read.’ She stressed that pruning down the stories she shared was an extremely emotional process for her, because “I feel like I still carry their stories with me all the time. They shared so much of themselves that I really felt that I owed them to tell their stories.”

Overarching Themes Expressed by Caregivers

When I asked Deborah whether any themes emerged when speaking with family caregivers, she noted that there were several:

“Yes, the first was control, a theme that really permeated every conversation: the feeling of loss of control. As you grow up, you develop a profession, you buy a house, you get married, and somehow you start believing that you actually have some control over your life. Then, all of a sudden, when you’re told that you or a loved one has cancer, that sense of control is gone. That theme was particularly significant for some of the male caregivers. I had a couple of them who described themselves as control freaks who had to learn to let go of the fiction that they had any control.

“The second theme was the need to somehow preserve hope and, even for those who were told that they were in very dire straits, to see their situation in a more positive light. When one was told that x percentage of people only survive a certain period of time, she and her husband said, ‘Fine: we’ll be in the other percent.’ Even if it was a mind game, these caregivers found some way to create some hope in the situation, but also to make sure that today was a joyful day, that there was something today that I could do to help the person not just get through the day, but really enjoy the day. And for many of them, that was hard. But you know, there were several stories of people dying at home, where even the death experience was turned into something that would feel positive and in their control, as opposed to being in a hospital, where you couldn’t control who was coming in and giving you shots and doing all sorts of things.

“The third theme was isolation–the feeling that so many of the caregivers had of being cut off from the people they used to see often. I called those people ‘pull-aways,’ the friends who didn’t know what to say or do, and so didn’t talk about it or didn’t make contact as they might have back before the cancer diagnosis. And there were some situations where the patient was too sick to go out, and so the caregiver’s solution for overcoming isolation was to invite friends in, but to be very clear about when it was time for them to go. The caregiving experience changed caregivers’ social patterns, but they really felt its absence unless they invented new ways to interact with friends.

“[Another important] piece was normalcy. People wanted so badly to get back to normal, and yet there was never going to be a normal again. Maybe a new normal would evolve, but life would never go back to the pre-cancer world.”

Deborah also noted that when reflecting on their experiences as caregivers, “All noted that their caregiving had enriched their lives. It really did. And I was really surprised when I asked them, ‘How are you different?’ I just didn’t know what I was going to hear. It was encouraging and also really striking how many of them engaged in an activity that will in some way give meaning to their caregiving experience, particularly if their loved one died. Even though this matched my own experience, I didn’t realize just how widespread that giving-back phenomenon would be. Sometimes it’s focused on a specific type of cancer, such as leukemia or lymphoma. Sometimes people actually created a new foundation, like two caregiving families living next door to one another who together created a brain tumor organization to benefit a local hospital, for example. It’s fascinating to hear the creativity people use in determining how to get involved and how they want their loved one either to be honored or remembered.”

I asked Deborah if hearing such emotionally trying, heartfelt stories was ever difficult for her both as an interviewer and as a cancer survivor herself. She agreed that it was: “A couple of times, I did break up on the phone, and I apologized. But I found it didn’t matter to the interviewee. In fact, it revealed that I cared. I always felt self-conscious about it, but it turned out to be okay. To have them talking about the last minutes of somebody’s life and to be able to do so in such a loving and really clear descriptive way, it was hard to imagine putting myself in their shoes and being able to have gone through what they experienced with as much grace. They really all gave a tremendous gift to me and to anyone who reads the book, because of the raw emotions that they shared. Equally riveting were their descriptions of their lives afterwards and how they have healed. I’ve actually written an article about healing and added some of these insights into the second edition of the book, because I think it’s really helpful to those who are still going through the process.”

Starting the Healing Before the Caregiving is Over

“One of the important things I learned was that people who do it well start the healing process before the caregiving is over,” Deborah stressed. “And in fact, in some cases, the patient actually helps start that process. One young man whose mother died described one of her last days, [when she gave] him instructions about how she wanted to be buried. She asked him to make sure that she was wearing nothing but her full-length mink coat and red high heels! And that’s what he did. He can still laugh now when he talks about it, because it was such a funny funny request and reflected so much about her personality. The other thing she had done that was so fascinating: as an experienced oncology nurse, she surrounded him with many of her nurse friends, so that if he ever had any questions as she was going through treatment, he had this network that could be a safety net for him. There were several examples of patients who had done something like that. It turned out to be really important to each caregiver’s healing later.”

The Keys

I couldn’t let Deborah go without asking her about the cover design for her book. As shown below, the cover displays three large, antique keys that immediately grab the eye. She explained that “I’d looked at several alternatives, [but] this was the one that struck me. I think that the keys have meaning in the sense that … it’s almost like there are trap doors throughout the caregiving process. And knowing what door to open and which key to use, it was almost an analogy of finding answers–‘What’s behind this door? What’s behind that door?’ There are hidden things that you need to find out behind each door. The key design was really the message of the book and the best way to show it. Somehow it spoke to me.”

Messages from the Caregivers

What better way to conclude than sharing the words of some of the caregivers from “Things I Wish I’d Known: Cancer Caregivers Speak Out”?

“Professional caregivers don’t experience the emotional ups and downs that a family caregiver does. The family caregiver truly bears the brunt to support the patient in the right ways, not too much or too little. It’s critical for the patient’s progress.”

~Ellen M, registered nurse and cancer survivor, sharing her perspective on the role of her husband as caregiver

“Caregivers have a difficult emotional time. They don’t face the daily adrenaline surge that the patient does, but they have to pick up the pieces when things aren’t going well. It’s hard for them to know when to reach in and when not to. They walk a tightrope between letting the patient be in control and being able to take care of them without letting their loved one feel incapacitated. Caregivers haven’t experienced the physical pain, but they also can’t make it go away. The caregiver has to be strong, but not overpowering; sympathetic and optimistic, but not saccharine; realistic but not discouraging; upbeat but not inappropriately happy.”

~ Bobbi, long-time breast cancer survivor, articulating the challenge of caregiving

“There’s no better way to learn about dealing with cancer as a caregiver than hearing other people’s stories.”

~ Debbie B’s husband

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Book

Interested readers can locate Deborah’s book in paperback or electronic forms at the following websites:

“Things I Wish I’d Known: Cancer Caregivers Speak Out”

Amazon.com

Barnes & Noble

Deborah stressed that the sourcing of interviewees was itself a fascinating process. “I think the most interesting piece of it was that in addition to posting invitations at several of the Hope Lodges, I would also send out waves of emails to groups of my own contacts, asking them to spread the word. I got a phone call one day from a woman who had received my email, which I’d sent to someone out of state, who forwarded it to somebody else in another state, who in turn forwarded it to the woman who called me. It turned out that on the third forwarding, it went to [this woman] who lives five minutes from my house! Isn’t that bizarre? So there are all sorts of fascinating procurement stories in terms of finding these people.” Deborah went on to share another example of such serendipitous connections: “I received a phone call from a woman who had just lost her husband. [She’d been] in a park walking with her daughter and newborn son, and a friend of mine happened to be passing through that city when they met and created the connection. This woman has sustained our relationship and become a good friend. There were all sorts of really random types of connections, but essentially, when I got to 86—and there was nothing magic in the number–I thought to myself that I’m hearing the same things frequently enough that I believe I have enough to work on. So that was the genesis.” In the second edition of the book, Deborah added another nine conversations focused on healing, bringing the total to 95.

Deborah stressed that the sourcing of interviewees was itself a fascinating process. “I think the most interesting piece of it was that in addition to posting invitations at several of the Hope Lodges, I would also send out waves of emails to groups of my own contacts, asking them to spread the word. I got a phone call one day from a woman who had received my email, which I’d sent to someone out of state, who forwarded it to somebody else in another state, who in turn forwarded it to the woman who called me. It turned out that on the third forwarding, it went to [this woman] who lives five minutes from my house! Isn’t that bizarre? So there are all sorts of fascinating procurement stories in terms of finding these people.” Deborah went on to share another example of such serendipitous connections: “I received a phone call from a woman who had just lost her husband. [She’d been] in a park walking with her daughter and newborn son, and a friend of mine happened to be passing through that city when they met and created the connection. This woman has sustained our relationship and become a good friend. There were all sorts of really random types of connections, but essentially, when I got to 86—and there was nothing magic in the number–I thought to myself that I’m hearing the same things frequently enough that I believe I have enough to work on. So that was the genesis.” In the second edition of the book, Deborah added another nine conversations focused on healing, bringing the total to 95.